Zhu Di, the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, relocated the capital from Nanjing to Beijing and built a new imperial palace there. This palace was a complete copy of the Nanjing Palace. This Ming Palace in Beijing is now the Palace Museum. While the Nanjing Ming Palace was built first, the imperial city later followed. The Beijing Ming Palace and the imperial city were built together. Within the Beijing imperial city, there were gardens on the east and west sides of the palace, also modeled after the Nanjing Ming Palace. These two gardens were called the West Garden and the East Garden. The West Garden is now Zhongnanhai, while the East Garden no longer exists.

The West Garden was a place for the emperor to enjoy himself, boasting a large pool. The East Garden was dry and was used by the emperor for leisure. The East Garden originally housed the Hongqing Palace, also known as the South Palace, which Zhu Di built as the Crown Prince's Palace. It is unknown whether Zhu Di's son, Zhu Gaochi, ever lived there. In fact, the palace was originally the residence of Zhu Di's grandson, Zhu Zhanji, and should have been called the Imperial Crown Prince's Palace. Because the Nangong served as the Crown Prince's palace, it was also called Chonghua Palace, a reference to the line in the Book of Documents: Shun Dian: "This Shun was able to succeed Yao, and cherish his radiant virtues." The "chong" in Chonghua is used to convey a sense of weight, not repetition. Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty adopted this meaning and renamed the West Second Wing of the palace, where he resided as a prince, Chonghua Palace after its renovation. According to both official and unofficial historical records, after Zhu Gaochi's son Zhu Zhanji, his grandson, Emperor Yingzong Zhengtong of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Qizhen, did reside in the Nangong Palace. In the 14th year of the Zhengtong reign (1449 AD), Emperor Yingzong personally led an expedition against the Oirat Mongols. During this period, he was framed by the eunuch Wang Zhen and abducted by the Oirat army during the Battle of Tumu. Since the country could not remain without a ruler for a single day, Zhu Qizhen's half-brother, Zhu Qiyu, was entrusted with the important task of emperor, becoming the Jingtai Emperor, or acting emperor. A year later, the Oirat released Zhu Qizhen without charge. His younger brother, Zhu Qiyu, was displeased with his brother's return. He declared to his ministers, "You appointed me emperor; he can only become the retired emperor upon his return." He then imprisoned Zhu Qizhen in the Nangong Palace in the East Garden. It's said that the walls and doors were so tightly shut that only a small hole was left to allow food to pass through. The hole was so small that only noodles could be slipped in one by one, and steamed buns had to be broken into crumbs to be stuffed in. This is where the term "crushed" (渣渣) comes from. Seven years later, in the eighth year of the Jingtai reign (1457 AD), Zhu Qiyu suffered a stroke and lay bedridden. Supported by his former subordinates, Zhu Qizhen staged the Nangong Incident and ascended to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, resuming the throne as Emperor Yingzong. Upon his return, Emperor Yingzong exiled Emperor Daizong to the West Garden, where he died within two months. Zhu Qiyu was not buried in the Tianshoushan Imperial Mausoleum in Changping, but instead was buried at Jinshankou on Yuquan Mountain, where a royal mausoleum was built.

After several generations, it was Zhu Houcong's turn to become the Jiajing Emperor of the Ming Dynasty. He enjoyed alchemy and wanted to find a quiet place outside the palace to secretly refine elixirs. The treacherous minister Yan Song slandered the Nangong Palace, saying it was quiet. When the Jiajing Emperor saw Yan Song sending him to the unfortunate place where his ancestors were imprisoned, he became wary of Yan Song. Finally, he found someone to report Yan Song for breaking the law and had him executed.

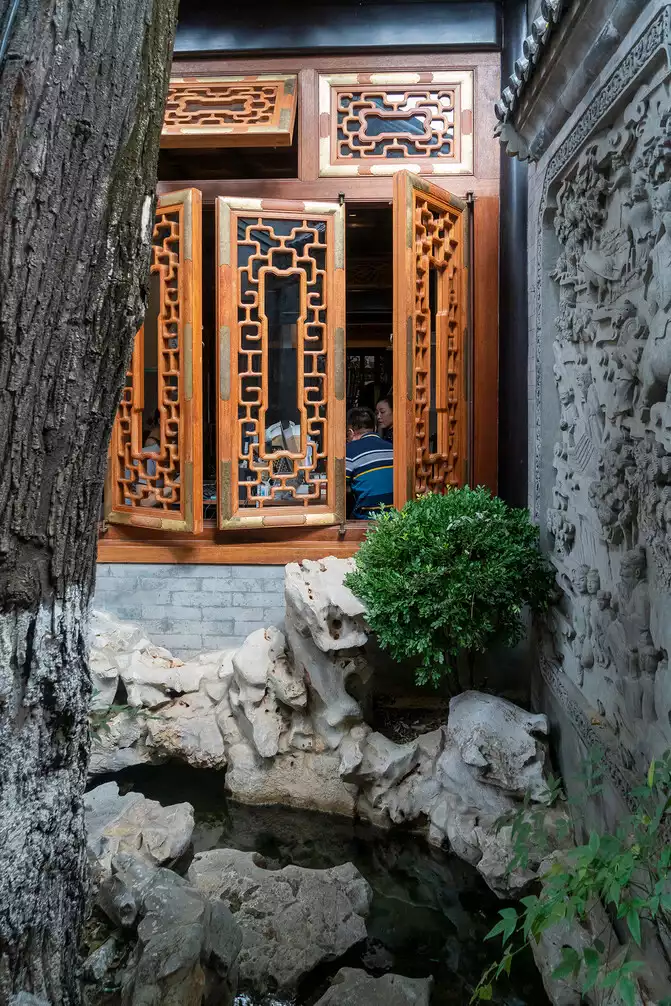

During the Ming Dynasty, ever since Emperor Yingzong of the Ming Dynasty suffered persecution and lived there, the Nangong Palace had been disfavored by the current Ming emperor and fell into decline. In addition to the Nangong Palace, the East Garden also had the Imperial History Hall built during the Jiajing period. It was a large brick and stone hall with a beamless arched roof, which stored royal historical materials during the Ming Dynasty. At the end of the Ming Dynasty, Li Zicheng, the King of Rebellion, invaded Beijing and occupied the palace, working in the Wuying Hall. After a few days, he could no longer work, so he set several fires in the imperial city and fled west. One of these fires was set in the East Garden, destroying it. When the Qing army entered the city, Dorgon escorted Emperor Shunzhi Fulin and Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang to the imperial palace. Fulin was still young, so the Empress Dowager asked Dorgon to take charge of government affairs. Regent Dorgon was known as Prince Rui. To facilitate his regency and visit Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang and her son, Dorgon led his personal guards to clean up the fire in the South Palace of the East Garden. He then built his Prince Rui Mansion on the ruins of the South Palace and rebuilt the main hall of the South Palace, where Emperor Yingzong of Ming slept, into his bedroom. In the seventh year of the Shunzhi reign (1650 AD), Dorgon led his troops out of Gubeikou to hunt wild boars at Bashang. Unfortunately, he was injured and died. Some say Dorgon died from a fall from his horse, but according to secret reports, a guard's crossbow accidentally discharged, striking Dorgon in the heel. Shunzhi initially treated Dorgon well, bestowing him the title of Chengjing Emperor and posthumously honoring him with the title of Emperor Chengzong of Qing. However, soon after, someone publicly accused Dorgon of numerous high treason crimes. Shunzhi revoked his title, exhumed his grave, and disinterred his body. The Ruiwang Mansion was also confiscated. During the reign of Emperor Kangxi, the abandoned Ruiwang Mansion was converted into a lama temple. It wasn't until a hundred years later, in the 43rd year of Emperor Qianlong's reign (1778 AD), that Emperor Qianlong fully rehabilitated Dorgon and rebuilt the former Ruiwang Mansion lama temple into the Pudu Temple. While the Western Garden was rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty, the Eastern Garden remained unrenovated. After Dorgon's Ruiwang Mansion, the Eastern Garden became the Qing imperial treasury. In addition to the Ming Dynasty archives, the Imperial History Palace, a silk and satin warehouse, a lantern warehouse, and a porcelain warehouse were also built. The Eastern Garden retained the Ming Dynasty's Imperial History Palace, while the Southern Palace was converted into the Pudu Temple. In the early Qing Dynasty, a small temple called Pusheng Temple was built east of the Imperial Archives. Pusheng Temple houses two of Beijing's only two horizontal merit steles, both extremely rare. One commemorates the temple's founding during the Shunzhi reign, and the other commemorates its renovation during the Qianlong reign. They are now located in Wuta Temple, north of the zoo. Why Wuta Temple? Because Pusheng Temple no longer exists; in 1915, it was converted into the current Western Returned Scholars Association. The Ming Dynasty East Garden gradually declined during the Qing Dynasty, becoming a royal storage facility. During the Republic of China era, officials from all walks of life occupied rooms there. High-ranking officials of the Republic of China resided in the various Qing-era princely palaces, while lesser officials found their own residences throughout the city. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, these Republican officials were relocated, and their quarters were seized. Military commanders and local leaders now resided in the Ming Dynasty East Garden. Today, walking along Nanchizi Street, you can see courtyards with garages, but these are not ordinary people's homes. In recent years, Pudu Temple has undergone some renovations and is now reopened. Residents of the surrounding area are welcome to play for free, and mothers sit under the trees knitting. The last time I visited, the mountain gate and main hall were still in place. The main hall is open to the public when there's an exhibition. The main hall was rebuilt during the reign of Emperor Qianlong after Dorgon's rehabilitation, and it still features the Qing Dynasty style. The mountain gate dates back to the Kangxi era and is similar to other small Qing Dynasty temples in Beijing, such as Songzhu Temple on Shatan North Street near the Red Building of Peking University. The ancient Chinese urban layout originated in the lifang system of the Xia and Shang dynasties, reaching its peak during the Sui and Tang dynasties in Chang'an. This pattern can still be seen in some ancient villages in Shanxi. Later, during the Northern Song Dynasty, the urban layout evolved from the lifang system to the street and alley system, which continues to this day. For examples of preserved and restored streets and alleys from the Ming and Qing dynasties, see Fuzhou's Three Lanes and Seven Alleys, which I visited. Old Beijing was a classic street and alley system, and the Ming Dynasty Dongyuan outside Donghuamen is no exception. Despite renovations during the Qing Dynasty, haphazard construction during the Republic of China, and the haphazard construction of recent decades, traces of the streets and alleys of old Beijing can still be seen. Beijing's alleys are also called hutongs. In the area outside Donghuamen, you can find names like Nanchizi Street, Pudu Temple Front Lane, Duanku Hutong, and Ciqiku Hutong, encompassing both main streets and small alleys. Nanchizi Street ends south of East Chang'an Avenue, and on the west side of the intersection, there used to be the Chang'an East Gate. East of the intersection of Nanchang Street, west of the Forbidden City, was the Chang'an West Gate. Chang'an Avenue's name comes from these two gates, which were demolished in the 1950s. In the documentary "The Founding Ceremony of the People's Republic of China," you can see footage of troops parading through the Chang'an East Gate. Get off at Tiananmen East Station on Metro Line 1 and walk north along Nanchizi Street to the former Ming Dynasty East Garden. You'll see a sign for Pudu Temple Front Lane on the east side of the road. Enter and visit Pudu Temple. Continuing north, you'll see a sign for Pudu Temple West Lane on the east side. Enter this alley, turn north at the end, and you'll see a small gate built into the west wall. This is the Nanchizi Art Museum I'm visiting today. Tucked away in the bustling city, it feels like a hidden gem. This museum was recently renovated. Like the Pudu Temple main hall nearby, it's closed to the public, opening only during exhibitions. Currently, it's hosting the "Heavenly Dao: Taixiangzhou Ink Painting Exhibition," which runs until September 20th. This small gate is never open. If you have a reserved ticket for an art exhibition, you can ring the doorbell, and the door will open, revealing a beautiful woman. The brick door, stone frame, checkerboard-style doors with brass sashes, and old-fashioned knockers create a simple, understated aesthetic. The lack of a doorpost suggests this is a side door, not the main gate. The lintel is engraved with the character "某涓." I can't quite make out the character, but it might represent the family name of the owner, who didn't want to reveal it publicly. The character "涓" suggests water within, but don't let your imagination fool you; the water inside definitely isn't the "pond" in the South Pond.

Enter and take in the entire garden. A clear pool of water lies within. According to the ancient belief that a round shape is a pond and a square shape a swamp, this should be called a fish pond. Following the Beijing courtyard style, several houses are built around the fish pond. To the north lies the main house, with wing rooms to the east, a corridor to the west, and a back house to the south. From the front, the north house is three bays wide and one bay deep. The main room features four partition doors, while the east and west side rooms have sill-walled windows. A veranda stretches to the front, and beneath the columns and crossbeams are carved wooden corbels without cloud piers. Above is a raised-beam, gray-tiled, hip roof. A gray-tiled, single-eaved, hip roof with a Qing Dynasty-style gargoyle can be seen behind. In front of the house, facing the water, stands a small white stone platform with a carved wooden staff railing. The columns, beams, and rafters are all painted black, a telling feature. The main house has a large opening, much larger than a private residence, but not as large as those in a royal palace. The pillars are painted black, unlike the red lacquer of the imperial court and the green lacquer of the royal palace. This suggests that the owner of this courtyard was probably below the provincial or ministerial level, roughly equivalent to a prefectural governor in the Qing Dynasty.

This turns out to be the inner and outer rooms, separated by a shrine in the middle, flanked by moon-shaped doors. Look above the front room.

The raised-beam structure is exposed from top to bottom, with a single arch. Now let's take a look at the inner room.

Above is a flat chessboard ceiling, white with no patterns, neither cranes nor peonies. It should be the single-arch, single-eaved hip roof seen from the outside, so the inner and outer rooms should have double-arched, connected roofs.

The main room is the main hall of this exhibition. On the north wall is a set of eight-panel screens, "Parallel Universes III," a relatively rare sight; four-panel screens are more common. On the back of the shrine is the exhibition's title painting, "The Way of Heaven, the Dark and the Bright." Both the shrine and the moon gate are covered with auspicious wood carvings. Look at the carving on the side of the shrine below. There are five magpies on the plum tree; this is called "Joy on the Eyebrows," a symbol of overwhelming auspiciousness. To the east of the main room is an annex where staff members are housed. It's unclear if the artist himself is there, but he could always step out from the main room to discuss his painting skills and ink-wash cosmology with the audience.

After leaving the north room, you can stroll along the corridor on the right.

Take a look inside and outside the west corridor.

Having just exited the north door, I entered the deep west corridor. If I could set up some wine beneath the west corridor, I would wait for the moon to flow through more than ten thousand cups, and send off the gods with a towel and a cane.

In the corridor, facing inward, are partitioned windows, inviting you to enjoy the view.

There are frosted glass windows facing outward to prevent thieves from peeping.

This window is painted with bananas, apples, large pears, and an octopus. The next window must be painted with cigarettes, matches, osmanthus candy, and a pangolin.

There is a pavilion with a waterfront in the middle of the corridor.

Behind the pavilion, there is a door on the west wall. This means that behind this door lies the main courtyard of the house. Here, we are referring to the owner's East Garden. While private gardens are often located behind the main courtyard, it's also possible to build them on the east or west side. Standing in the open veranda and looking across, you'll see the East Wing. The East Wing is similar to the main house, three bays wide and one bay deep. It features a raised-beam structure with gray tiles and a hip roof. There's a partition door in the main room, and partition windows on the sill wall of the secondary room. The east wing is certainly lower than the main room, with a slightly smaller span. It lacks a front porch and, of course, a platform.

Take a look at the south room.

Like the north room, the south room is three bays wide and one bay deep, with a gray tiled, hipped roof. The north room has a front porch, while the south room does not. It also has a platform. In front of the south room is a pavilion with a waterside terrace. The roof ridge above this pavilion is different from the others; it has a "rolled roof," also known as a "tilted corner." This type of "rolled roof" isn't commonly used in northern China today, but is more common in the south. It's an ancient architectural element that originated in the Qin and Han dynasties.

Standing in the south room, looking north. The south room also houses an exhibition hall. At the base of the opposite east wall is the centerpiece of this exhibition hall: a piece of Taihu Lake stone. The exhibition room features artwork inspired by the artist's appreciation of rocks, combining both illustration and text. China has a long history of appreciating rocks. Emperor Huizong of Song, who lost his country, was a master of this art. He collected various rare stones from the south, assembled them into a "Flower and Stone Gang," and transported them to Bianjing to build the Genyue Temple. Many of these rocks were porous limestone from Taihu Lake, hence the name Taihu Stone. When the Jin invaders captured Bianjing, they not only abducted the two emperors, Huizong and Qinzong, but also demolished Mount Genyue and shipped a large quantity of its rare stones to Beijing. They used these stones to build Qionghua Island in the imperial gardens outside the city, which is now Beihai Park.

Take a look at the sash windows in the south room.

Except for the three-panel sash windows in the main room of the north room, all other rooms in the garden have windows like the one above, known as floor-to-ceiling double-panel sash windows, with latticework in a cloud pattern. A half-warming room has been partitioned off in the west of the south room, where a set of traditional Chinese camphorwood wardrobes have been built into the wall. Ordinary families often used camphorwood boxes to store valuable clothes to protect from insects, while wealthy families used camphorwood for wardrobes. In the past, if someone's cash flow was cut off, they would pawn their fur coats. The pawnshop owner would pick up your fur coat, shake it, and say, "This fur coat is covered in insects and rats." Your fur coat was taken from a camphorwood box, and there were no insects or rats to bite it. The pawnshop owner said this to lower the price. This warm room has a door that leads directly to the west corridor. Take a look at the door. The fake rosewood is actually elm. The brass facing has a stamped cloud pattern, called "lead-forged facing," and is considered quite high-end. The palace's lead-forged facing features not only cloud patterns but also dragons. Using facing to reinforce mortise and tenon joints is called a lock. The palace's facing is gilded, known as a "golden lock for doors and windows," while the ones here are brass locks. Look at the wood relief on the skirting: a river below, a mountain beside the river, orchids, chrysanthemums, and lotus at the foot of the mountain, and an eagle on guard duty on the mountain—an auspicious symbol of great auspiciousness. Building a house in a garden is merely necessary; to achieve class, more scenery is essential. Planting trees in a courtyard is essential, and in Beijing, locust trees are a must.

This locust tree was definitely not planted in the past two years, nor did it originate during the Qianlong era, but it's certainly quite old.

An old house sits by the pond, and behind it stands an ancient locust tree. Sophora flowers fall in the wind, rippling the pond water.

Where there is water, there must be lotus.

As summer fades, the late lotus leaves stand alone beside the pond. Their solitary beauty, unadmired by itself, often draws pity and admiration from visitors.

On the west corridor, there's not only an open waterside pavilion but also a small pavilion. Beside the pavilion, a tree bears unusual fruit. When asked where the fruit came from, the staff replied, "It's ornamental papaya, not edible." Seeing such a southern fruit in the capital is truly remarkable. An elegant garden cannot be without stones. There are two types of stones used in Chinese gardening. One is the Taihu rocks mentioned above, which are piled up to create a mountain landscape. The other is flat stones, which are also stacked to create a mountain landscape. This garden features both types of stones, either piled at the corners of the house or stacked in the water. The most majestic thing is a mountain range in the southeast.

The most majestic thing is a mountain range in the southeast.

On the mountain range stands a round pavilion. This reminds me of the six-pillar "Jinyue" pavilion in He Garden in Yangzhou, located in the same location and style. At the Spring Breeze Pavilion on Chunfeng Ridge, the spring breeze blows through the clear, sunny spring sky. Tomorrow, I'll listen to the spring rain in the pavilion, and drink with friends to indulge in springtime romance. The small courtyard of the Nanchizi Art Museum isn't as opulent as the gardens of a princely mansion, but it's exquisitely designed and elegant. Beijing boasts numerous princely mansions, including the vast gardens of Prince Gong's Mansion and Prince Chun's Mansion, where Soong Ching Ling once lived. Even the Grand View Garden, described by Cao Xueqin in "Dream of the Red Chamber," is quite large. I suspect the former owner of the Nanchizi Art Museum garden was a former divisional and brigade commander under Fu Zuoyi, a relatively minor official. The garden appears to have been rebuilt, and the main courtyard to the west is likely still inhabited. The buildings within the garden are neatly arranged, reflecting the architectural style and specifications of traditional Beijing residences, distinct from the Jiangnan gardens of Su and Yang. Not far from here, behind the National Art Museum of China, there used to be a Half-Acre Garden. This was the residence of Jia Hanfu, the former governor of Shaanxi during the Kangxi era, and the work of the garden master Li Yu. Though called Half-Acre Garden, it actually encompassed over ten acres. Demolished in the 1980s, it is now reproduced at the National Museum of Chinese Gardens and Gardens, a masterpiece of northern gardens. The Nanchizi Art Museum here doesn't specify how many acres it encompasses, but it's probably only half an acre. Despite its small size, it boasts pavilions, terraces, ponds, rocks, pines, locust trees, lotuses, and plum trees, creating a vibrant and picturesque scene. While its layout may seem dense, it's not cluttered. In short, the Nanchizi Art Museum epitomizes the northern garden and is well worth a visit. The quiet summer sun sets in the courtyard, its green shade blanketing the ground with lost spring flowers. Dreams of spring drift to the horizon.

Swallows fly beneath the eaves of the rocky railings, frogs croak among the lotus pond. Drinking wine, the bright moon shines through the window screens.

Number of days:4 days, Average cost: 2000 yuan,

Number of days:4 days, Average cost: 4,000 yuan, Updated: 2020.08.19

Number of days: 1 day, Average cost: 120 yuan,

Number of days: 2 days, ,

Number of days: 1 day, Average cost: 138 yuan,

Number of days: 2 days, Average cost: 1,000 yuan,