After Beijing became the capital, its economy developed greatly and its population increased greatly. Gradually, the city could no longer accommodate the population, and the capital's territory began to expand outside the city gates. When we say it expanded outside the city gates, it mainly concentrated on both sides of the streets outside the city gates, such as Zhengyangmenwai Street. In this way, bulges similar to tumors formed on the outside of the city gates. These bulges were called "guanxiang", where "guan" means the city gate and "xiang" means the surrounding area, such as the wing room. In the past, there were small areas called "guanxiang" outside the inner city gates, such as Anwai Guanxiang and Chaowai Guanxiang. These "guanxiang" are no longer mentioned today, because all the guanxiangs are connected and no longer individual bulges. Only the place name "Dewai Guanxiang" remains, and people often mention it. Bus No. 55 still has a stop at Dewai Guanxiang, and then goes to Qijiahuozi, which is a gap in the earthen city wall during the Yuan Dynasty. Over a hundred years after Zhu Di relocated the capital, the Guanxiang area had become highly developed. Not only did people own houses, but crucially, they also contributed taxes to the imperial court. At this time, the Mongols from the north frequently harassed Beijing. While the city walls provided ample defense, those outside were subject to looting. During the Jiajing reign, these raids intensified. Someone proposed to the Jiajing Emperor the construction of an outer city to enclose the Guanxiang area, and the emperor approved it. Initially, the plan was to build an outer wall along the original walls of the Yuan capital, but this proved prohibitively expensive, and the government had limited silver reserves. So, the solution? Construction began on the most important areas, ultimately enclosing the southern section, where taxes were most heavily collected. This became the outer city wall outside the Qiansanmen Gates. This section of the wall now forms the southeast, south, and southwest sections of the Second Ring Road. Thus, the entire perimeter of Beijing's city walls now encompasses the entire Second Ring Road. After the outer city wall was completed, several gates were built, each equipped with towers, watchtowers, and barbicans, just like the inner gates. These gates are Guangqumen to the east, Guang'anmen to the west, and Zuo'anmen, Yongdingmen, and You'anmen to the south. Two smaller side gates were also built at the east and west ends of the inner city wall, later known as the East and West Bianmen. The West Bianmen is located on the north wall of Jin Zhongdu, which provides a rough idea of its location. Construction of the southern outer city wall began in 1553 (the 32nd year of the Jiajing reign of the Ming Dynasty) and was essentially completed by 1564 (the 43rd year of the Jiajing reign), allowing the removal of the blue iron construction fences. When the Second Ring Road was built, the outer city walls were demolished, including the outer city gates. In 2004, Beijing launched the application for World Heritage status for the Central Axis, and the Yongdingmen tower at the southern end of the axis was rebuilt to its original appearance. A central axis marker is also installed on the ground inside the gate. Looking north along the city gate, you can see the Zhengyangmen Arrow Tower in the distance. Above the arrow tower is the roof of the Zhengyangmen City Tower, and behind it is the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall.

This road is flanked by the Temple of Heaven on one side and the Temple of Agriculture on the other. Standing on this road, look south and see the Yongdingmen Tower.

Several evergreen pines are planted on either side of the tower.

The afternoon sun hangs on a corner of the city wall.

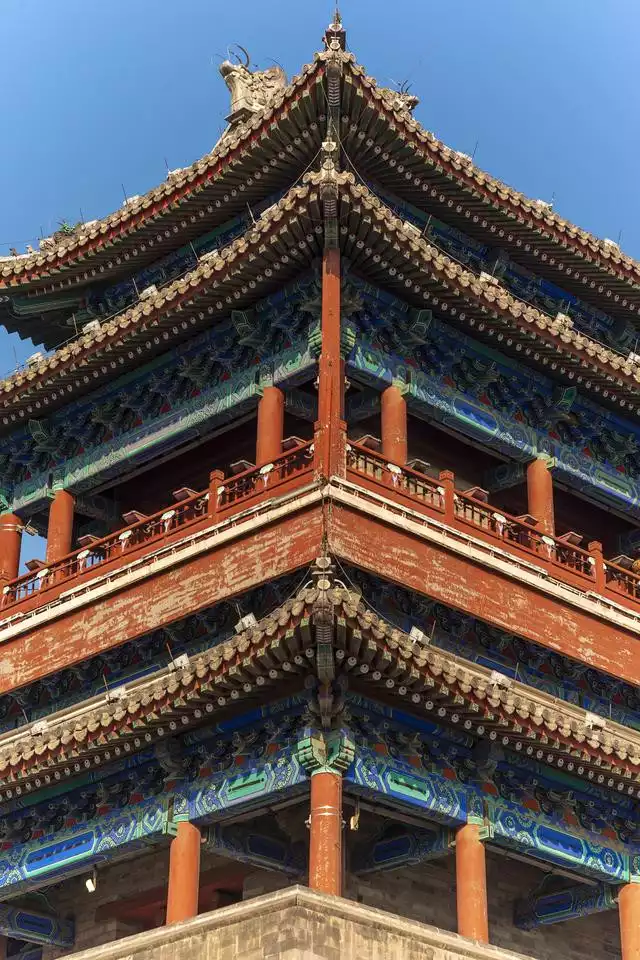

Look at its front. The lower city platform is actually three towers connected together, giving it a resemblance to the towers at Chongwenmen. Atop the platform is a two-story pavilion with a double-eaved hip roof. The first floor is surrounded by a veranda; the second floor features a flat railing with corner supports. The pavilion is five bays wide and three bays deep, clad in gray tiles with a green glazed edging. The main ridge is not a gargoyle, but rather a dragon-headed beast, similar to that found on the Zhengyang Gate Tower and the Deshengmen Arrow Tower. The central arched gate bears a stone plaque inscribed with the words "Yongding Gate." The original Ming Dynasty plaque was unearthed at Xiannongtan a year before the tower was rebuilt. It dates back to the 32nd year of the Jiajing reign. The current plaque is a replica of the original, and appears to be written in the same regular script as the "Pingze Gate" plaque. There's also a wooden plaque on the gatehouse that reads "Yongding Gate," said to have been inscribed by the early Republican era calligrapher Shao Zhang. Judging by the calligraphy, I suspect the Zhengyang Gate plaque was also by Mr. Shao. Yongding Gate certainly symbolizes eternal stability. The South City was built to defend against the invasions of Mongol bandits, and these five new gates all symbolize peace and tranquility. Guang'an Gate was originally called Guangning Gate, but was renamed Guang'an Gate during the Qing Dynasty. The "qu" in Guangqu Gate also means "vast." Look at the lions in front of the gates; they weren't supposed to be there.

Look at the corner of the tower; it's very beautiful in the sunlight.

When Yongdingmen was rebuilt, the bricks that had been removed were found and rebuilt into the wall, so this is still the Ming Dynasty city wall. The rammed earth inside the bricks is not from the Ming Dynasty, and even if it was, it's not visible. The Arrow Tower was not restored, and of course, the Barbican was not restored either. The moat surrounding the barbican has been dug through and connected to the southern moat, now filled with water. The former barbican has now become a plaza. Residents can stroll and fly kites here. The only surviving gates of Beijing's old city are the Zhengyangmen Tower and its Arrow Tower, as well as the Deshengmen Arrow Tower in the inner city and the rebuilt Yongdingmen Tower in the outer city. The Second Ring Road was built along the Beijing City Wall. Beyond the Second Ring Road, there are the Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Ring Roads. So where is the First Ring Road? You're probably familiar with Beijing's "Imperial City Wall," and even the TV series "Imperial City Wall." Beijing used to be nested in layers: the Outer City, the Inner City, the Imperial City, and within the Inner City was the Forbidden City, the imperial palace. The Forbidden City itself has four gates: Wumen, Shenwumen, Donghuamen, and Xihuamen. The First Ring Road actually circles the Imperial City Wall, but it's so narrow that it can't be called a "ring road." Beijing is also known as the "Four-Nine City," referring to the common people's space between the nine gates of the Inner City and the four gates of the Imperial City. We've already discussed the nine gates of the Inner City, and we've even seen some ruins there. We're all familiar with the four gates of the Imperial City: Tiananmen, Di'anmen, Xi'anmen, and Dong'anmen. Tiananmen Gate still exists, but the other three gates are gone, having become mere place names. The imperial city begins at Chang'an Avenue, and eastward stretches to Nanheyan and Beiheyan Streets. The river referred to as "Heyan" is the Imperial River, the same one that connects to Zhengyi Road. Exit Donghuamen and walk east along Donghuamen Street to the intersection that separates the North and South Heyan streets. This is where the long-demolished Dong'anmen Gate stood. A few years ago, excavators uncovered the base of Dong'anmen's wall, more than two meters below the current surface. That must have been the foundation of the old city gate. The base of the wall was once yellow earth, but now it's paved with blue bricks, dating back to the Ming Dynasty. This is the site of Dong'anmen. The Ming Dynasty imperial city wall was originally located west of Nanheyan Road, with the Imperial River outside the city walls. This location, on the east bank of the Imperial River, is the result of the eastward shift of the imperial city wall during the Xuande reign. After the construction of the new Dong'an Gate, the original Dong'an Gate was retained and renamed Dong'anli Gate. A bridge over the Imperial River separated the two gates. After the Imperial River was covered, the area now became Nanheyan Street, with Donghuamen Street as the boundary. A green park has been built on the area where the city wall lies beyond the street. Further east is Dong'anmen Street, which continues to the north entrance of Wangfujing Street. The eastern wall of the Imperial City originally stood on the west bank of the Imperial River, which lay outside the city walls. Later, the eastern wall shifted eastward, enclosing the Imperial River within the city walls. Outside the city walls were the East Huangchenggen North and South Streets, with Wusi Street as the boundary. A tributary of the Imperial River within the city walls flows eastward from the Jinshui River in front of Tiananmen Square, along the inner walls of the city walls, to the intersection of Nanheyan Road, where it merges. The river then flows south through Zhengyi Road and into the South Moat. In 2002, this tributary was dredged to form the Ming River, creating a park called Changpu River. Don't make wild guesses; that bridge over the river isn't called Changpu Bridge. By the river, Passerby A is reading, and Passerby B is walking on the road. On the shore, citizens are playing the card game "Knock Three." On the opposite bank, a "stone from another mountain" rests, and behind it lies the southern wall of the Imperial City. Inside, idlers sit as still as virgins, while outside, cars race like rabbits on Chang'an Avenue. On the eastern side of the Imperial City, north of the Changpu River, stands the Imperial Archives, known as the "Huangshicheng," or "Cheng" ("Cheng"), pronounced "cheng." The Imperial Archives' main hall is a beamless stone structure, devoid of timber. Its brackets and beams are all carved in stone to imitate wood. It's warm in winter and cool in summer, perfect for storing books. Modern libraries often have dark, dayless storage rooms like these. Leaving the Imperial Archives and walking north along Nanchizi, there's an east-west alley called Pudu Temple Alley. Surely there's a Pudu Temple there, and indeed there is. The entire temple rests on a blue brick platform, with steps leading up to the main gate. During the Ming Dynasty, this vast area was known as Xiaonancheng, its full name Hongqing Palace, and also as Nangong. Nangong was originally built by Zhu Di for his grandson Zhu Zhanji as the Imperial Palace of the Crown Prince, making it the same age as the Forbidden City. In the 14th year of the Zhengtong reign (1449), Emperor Yingzong Zhu Qizhen personally led an expedition against the Mongol Oirat tribe, but failed to capture them and was captured. His younger brother, Zhu Qiyu, succeeded him as Emperor Daizong in Beijing and repelled the Mongol forces. A year later, in the first year of the Jingtai reign, the Oirat tribe released Zhu Qizhen. Emperor Daizong welcomed the retired Emperor at Dong'anmen. "The emperor met him at Dong'anmen, then entered Nangong, where all civil and military officials performed the court ceremony." After this, Ming Yingzong Zhu Qizhen resided in the Nangong Palace for seven years, effectively under house arrest. In the eighth year of the Jingtai reign (1457), following the Nangong Incident, Zhu Qizhen ascended the throne and changed the reign title to Tianshun. Ming Daizong Zhu Qiyu was deposed and placed under house arrest in the Western Garden, now Zhongnanhai. He died within two months at the age of thirty. The main hall of Pudu Temple was formerly the sleeping hall of Chonghua Palace in Xiaonancheng, the same palace where Zhu Zhanji rested when he was the crown prince. Ming Yingzong Zhu Qizhen also used this as his sleeping hall while imprisoned in the Nangong Palace. When Li Zicheng invaded Beijing in the late Ming Dynasty, the Nangong Palace was burned and abandoned. When the Qing army first entered Beijing, Regent Dorgon chose this ruined palace to build his residence, calling it the Prince Rui's Palace. The main hall of Pudu Temple still serves as his sleeping hall. After Dorgon's death by arrow, the palace was confiscated by Shunzhi. During the reign of Kangxi, the northern half of the palace was converted into a temple, and it was renovated by Qianlong. Pudu Temple was named by Emperor Qianlong. After becoming emperor, Qianlong renamed the West Second Residence, where he lived as a prince, Chonghua Palace. Therefore, Pudu Temple was the Chonghua Palace of the early Ming Dynasty, while after the reign of Emperor Qianlong, Chonghua Palace was located within the Forbidden City. "Chonghua" comes from the Book of Documents, Shun Dian, which states, "This Shun was able to succeed Yao, and to cherish the splendor of his literary virtues." Chonghua Palace is somewhat like the Qianlong Palace in Kaifeng Prefecture. The mountain gate of Pudu Temple has been preserved, similar to the one I saw last time at Zhusong Temple, but with green glazed tiles. Looking at the Mountain Gate Hall from behind, the glazed tiles on the roof are half new and half old. Are the old ones from the Qianlong era? Turn around and look at the main hall, the Tzu Chi Hall. This hall once served as a sleeping quarters for many people. From the front, the roof of the main hall has a Ming Dynasty style. Then, look from the side. Beneath the main hall stands a three-foot-high white marble pedestal, topped by a blue brick floor. This high standard, likely a Ming Dynasty foundation, was intended to accommodate the crown prince. Dorgon undoubtedly chose this location for his royal residence due to its high architectural standards, which was likely one of the charges cited by Shunzhi for depriving him of his throne. The main hall is five bays wide and three bays deep, with a single-eaved hip roof made of gray bricks and green glazed tiles. In front of the main hall was originally a spacious platform. After Emperor Qianlong rehabilitated Dorgon, he constructed three side porches on this platform, each with a single-eaved hip roof made of green glazed tiles and yellow glazed tiles. The main hall and side porches are surrounded by a veranda. This hall doesn't feature pillar-paneled windows, but rather blue brick walls. The glazed tiles at the base of the wall are quite unique: they aren't very tall, but their top edge is higher than the bottom edge of the windows. Mullioned windows of this size are extremely rare, found only in the Palace of Earthly Tranquility in the Forbidden City. Because the main hall of Pudu Temple is constructed of blue brick, such large windows are indeed necessary to enhance the natural light.

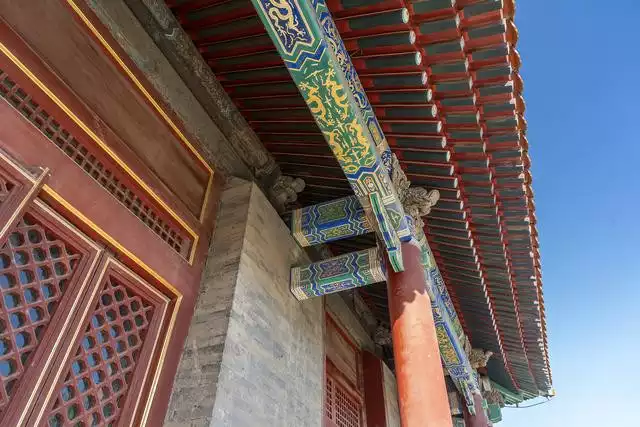

The roof isn't a bracket-type structure, but rather appears to be a through-beam structure.

Entering the hall, I saw that it was indeed a bracket-type structure. Above is a double dragon and Hexi-style chessboard ceiling, the older one dating from the Qianlong period. Between the rafters, several Qianlong-era paintings, each in a unique style, are adorned with horizontal scrolls. These aren't Hexi-style or Su-style paintings, but rather individual depictions of flowers, birds, fish, insects, bottles, jars, and even a tray of soup dumplings.

Look closely at those bottles and jars, especially the tray of soup dumplings. They're not Chinese paintings at all, but Western Baroque oil paintings, similar to the still lifes of 18th-century French painter Chardin. Although Western influences were said to have spread eastward during the Qianlong period, Western painting hadn't yet reached this place, right? This was a temple then. Were these paintings commissioned by Dorgon? That's impossible, as Western influences hadn't yet spread eastward. The ancient paintings on the horizontal scrolls inside this hall are fascinating! I spoke with the staff at the door, and he didn't know the origins or depth of these paintings. However, he did know about the new paintings currently on display. Currently on display are ink paintings by Mr. Fan Yuzhou, a painter of the splash-ink school. It's said that Mr. Fan is the 29th generation descendant of Mr. Fan Zhongyan. However, his paintings seem quite different from those of Mr. Fan's time, likely dating back more than 29 generations. In short, Pudu Temple boasts marvelous paintings. Thanks to Mr. Fan's marvelous ink painting exhibition, I had the opportunity to enter the main hall and see the marvelous ancient paintings on the beams. The staff at the gate said the main hall is usually closed, and you can only admire the exterior of the main hall and the mountain gate from the courtyard. Pudu Temple is now free to enter. The courtyard is a playground for children from the surrounding alleys. The children run around happily, while their mothers sit under trees browsing their phones, and no one knits. Occasionally, the main hall is rented for art exhibitions or other cultural events. After Shunzhi confiscated Dorgon's palace, it underwent a major renovation during the reign of Emperor Kangxi. The northern half of the palace was converted into a temple, which is now the remnant of Pudu Temple. The southern half was converted into various warehouses. Some place names within Chaoyang Gate contain the word "cang," and some alley names here also contain the word "ku," such as "lantern warehouse," "ciqi warehouse," and "duan warehouse." The above refers to the East Wall and the East Garden of the Imperial City. The North Wall of the Imperial City is located on present-day Ping'an Avenue, and the north wall of Beihai Park is a section of the Imperial City Wall. Di'anmen was located at the present-day Di'anmen intersection. The West Wall of the Imperial City is a bit more complex. The northern section is what is now Xihuangchenggen North Street, home to the famous Beijing No. 4 Middle School. Going south from Xihuangchenggen North Street is definitely Xihuangchenggen South Street. On Xihuangchenggen South Street stands the Prince Li Mansion, the residence of the descendants of Daishan, Prince Li of the Qing Dynasty. The Ministry of Civil Affairs once had offices there, and it is said that it now houses the General Office of the State Council. The dividing line between the north and south Xihuangchenggen Streets is Xi'anmen Street. From here, the West Wall of the Imperial City turns east and continues along the north side of Xi'anmen Street until it reaches the intersection with Fuyou Street. Xi'anmen used to be located on the Wenjin Street side of the Fuyou Street intersection. You see, Xi'anmen and Dong'anmen are not on the same line; Xi'anmen is located to the north. The western wall of the Imperial City runs east along Fuyou Street all the way to Chang'an Avenue. Beihai, Jingshan, and Zhongnanhai are all within the Imperial City. Along Chang'an Avenue, you can still see the walls of the former Imperial City, certainly the outer wall of Zhongnanhai, as well as the southern walls of Zhongshan Park and the Workers' Cultural Palace. Tiananmen Square is majestic and imposing, but the other gates of the Imperial City are simpler, lacking a platform; they are simply three-arched brick gates. The Imperial City contained imperial properties and services. Therefore, the "Four-Nine City" mentioned in old Beijing did not include the Imperial City. This gives you a clear idea of where the First Ring Road is. To the south is Chang'an Avenue; to the north is Ping'an Avenue; to the east were originally Nanheyan Street and Beiheyan Street, and later East Huangchenggen South Street and North Street; to the west are Fuyou Street, Xi'anmen Street, and West Huangchenggen North Street. Beijing's city walls have been demolished, leaving no trace. This isn't just for Beijing; the walls of foreign capitals were also long gone. The walls of Paris are gone, but I once saw the remains of one of its gates. The ancient Roman walls were also demolished, but what remains is a fortress on top of the walls, the Castel Sant'Angelo. After the walls of Madrid, Spain, were demolished, the site of the former gates became a square. This is Puerta del Sol.

It seems the city walls of Beijing, both Chinese and foreign, have suffered similar fates. Beijing has rebuilt one Yongdingmen tower, but building more would be incredibly difficult, and besides, unnecessary. The Yongdingmen tower was rebuilt to support the Central Axis' application for World Heritage status.

With this, we've covered Beijing's gates and walls, and even seen a few of their remains.

(End of series)

Number of days: 1 day, Average cost: 120 yuan, Updated: 2021.10.11

Number of days:6 days, Average cost: 5,000 yuan,

Number of days: 2 days, Average cost: 1500 yuan,

Number of days: 1 day, Average cost: 360 yuan,

Number of days: 1 day, , Updated: 2022.10.14

, Average cost: 20 yuan, Updated: 2021.04.02